WE ARE MANY.

WE ARE RAILFANS.

Railfan-Guest

October 7th, 2021

As a boy, my late father used to climb up to the signal-box to join his Uncle Harry, a signalman on the London & North Eastern Railway in Newcastle. Naturally, I inherited my Dad’s interest and he was delighted to receive copies of some of my first railway books. I now have sixteen titles in print, published by Amberley, and covering railway topics both local to me, and worldwide.

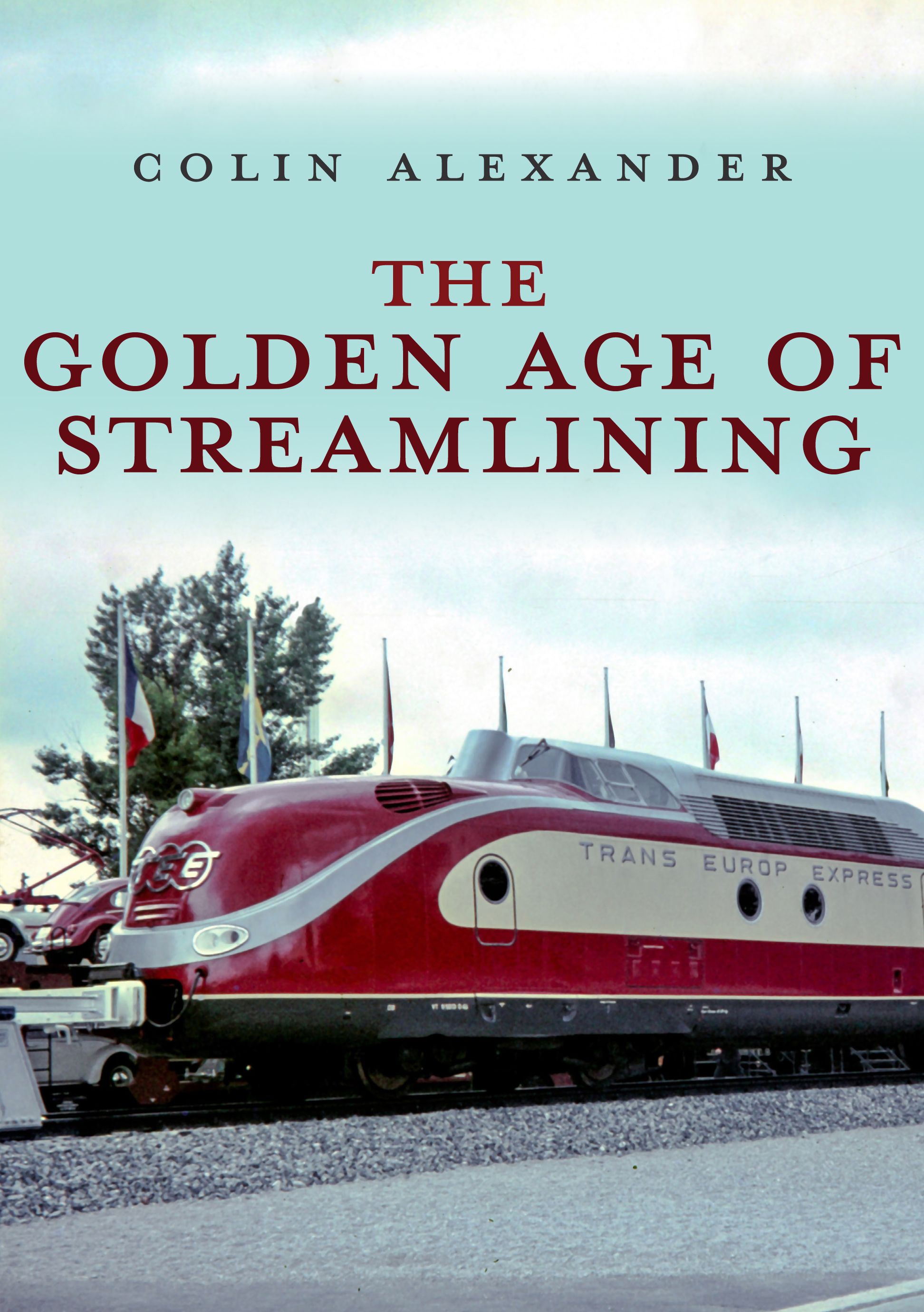

One of my favourites is The Golden Age of Streamlining. It encompasses air, road and sea travel, as well as the influence of that design movement on architecture, furniture, etc. As usual, though, the railway, and specifically the golden interwar age of glamorous, streamlined express trains, takes centre stage. As I am also a teacher of Design and Technology, I tried to combine the science of aerodynamics with the resulting aesthetics.

The theme of the 1939 New York World’s Fair was Building the World of Tomorrow. Here, streamline style was everywhere: General Motors had its own Highways and Horizons pavilion, featuring Norman Bel Geddes’ Futurama exhibit, a scale model of his City of 1960. This bold vision of the future showcased streamlined GM cars on broad motorways with sweeping intersections, between graceful, elegant skyscrapers.

The focal point of the World’s Fair was the 600-foot Trylon, a futuristic landmark drawing attention to the neighbouring 180-foot diameter Perisphere, containing Henry Dreyfuss’ City of Tomorrow. Also inside was Raymond Loewy’s Transportation of Tomorrow exhibition of yet more streamlined vehicles and even a Transatlantic rocket-ship.

One of the earliest essays in railborne streamlining, thirty years after the Rev Dr Calthrop’s proposed 'air-resisting train', was Charles Baudry's C Class of 1893, for the Chemins de fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée. They sported a distinctive coupe-vent, or 'wind cutting' fairing to smooth out the forward-facing surfaces of the cab, chimney and smokebox.

Similarly attired, aerodynamically, was the experimental Königlich Bayerischen Staats-Eisenbahnen (Royal Bavarian State Railways) Class S 2/6 no.3201. Built in 1906, she possessed some highly advanced external features, such as the curved skirt in front of the cylinders, the conical smokebox door, fairings on the chimney and dome, and the wedge-shaped cab front. These additions, together with her superheating and four cylinders, propelled her to a speed of 95.6mph, not bettered in Germany for thirty years. Despite their use in both France and Bavaria, these streamlined features would not be commonplace until much later in the 20th century.

A slightly earlier 'wind-cutter' than the Bavarian locomotive was the McKeen petrol-engined railcar in the United States. The first was built in Nebraska in 1905, and as well as the streamlined profile it anticipated other later streamlining motifs, such as the porthole windows, which were adopted for structural strength.

The most famous of the early European streamlined diesels was Germany’s Fliegender Hamburger of 1933, for the prestigious high-speed run from Berlin to Hamburg, which it covered at an average of 77mph, then the fastest in the world. Wind tunnel experimentation had been used to determine the optimum profile of the lightweight, articulated sets, and one of them reached 133mph on a test run.

Meanwhile, my Great Uncle Harry’s London and North Eastern Railway was considering a high speed diesel service on the Newcastle to London route, similar to the Fliegender Hamburger, and the German manufacturers were asked to submit proposals. The best average speed they could offer for their design was 63mph, due to speed restrictions and gradients en route. Sir Nigel Gresley, the company’s Chief Mechanical Engineer believed that steam power was superior. To prove it, he arranged a test run in 1934 with his Class A1 no.4472 Flying Scotsman, hauling six coaches, three times the capacity and weight of the German train, from Leeds to the capital. On this run, 4472 achieved the world’s first authenticated 100mph by a steam locomotive. A few months later, sister engine no.2750 Papyrus, with higher boiler pressure, did even better on a test run from the capital to Newcastle and back, reaching 108mph. Gresley knew that a streamlined version could do better still.

The LNER publicised a new four-hour service from Newcastle to London, with an average speed of 67mph. Always with an eye for publicity, the new train, in its eye-catching livery of silver grey, was called The Silver Jubilee, commemorating 25 years of the reign of George V. Gresley had studied the French Bugatti Autorail Rapide railcar and used its front profile as the basis of his A4, following wind tunnel testing. The valances over the wheels were the shape of a true aerofoil, as specified by Gresley after he studied drawings of the R101 airship, and an additional benefit of the aerodynamic front end is that at speed, drifting smoke from the chimney was lifted clear of the locomotive crew’s vision.

The comparative horse power needed to overcome the air resistance on a Gresley A1 and a that on a streamlined A4 was calculated, and it showed that at a speed of 60mph, the non-streamlined locomotive needed 97hp to cut through the air, whereas the A4 needed only 56. At 90mph the difference was far more pronounced, the A1 requiring a substantial 328hp, compared to the A4’s economical 190hp.

This streamlining was no mere cosmetic exercise, for the A4s were streamlined on the inside, too. The diameters and curvature and angles of all of the internal pipework, even the smoothness of the surfaces of castings, were designed to permit the smoothest possible flow of high pressure steam to the cylinders.

The Silver Jubilee was a triumph both mechanically and commercially, leading to the introduction of two further A4-hauled streamlined services, the Coronation and the West Riding Limited. Streamlined ‘beavertail’ observation cars were provided and fairings were placed between the coaches to reduce wind resistance around corridor connections. On a trial publicity run in 1935 the Silver Jubilee, behind no.2509 Silver Link, reached the unprecedented speed of 112½mph.

Not to be outdone in the publicity stakes, the LNER’s rival for Anglo-Scottish traffic, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, introduced its own glamorous streamliner in 1937, the Coronation Scot. Sir William Stanier designed the powerful 'Coronation' Class, with four cylinders to cope with the route's arduous gradients. He was against streamlining, feeling it was superfluous, but the company wanted the publicity being enjoyed by the LNER.

On a press run, no.6220 Coronation reached a maximum speed of 114mph. Sister engine 6229 visited the USA and was exhibited as the epitome of British engineering at the aforementioned New York World’s Fair of 1939. The bulbous, almost brutal streamlining of the Stanier engines lacked the grace of the A4s, and it was removed by the 1940s.

In Part Two we will see how Britain lost and regained the world speed record……

The New York World's Fair of 1939 showcased all that was best in streamlining. The people in this image are queueing on the Helicline which passes through the base of the landmark Trylon and leads into the Perisphere, containing Henry Dreyfuss’ City of Tomorrow and Raymond Loewy’s Transportation of Tomorrow exhibits. (John Van Noate collection)

The New York World's Fair of 1939 showcased all that was best in streamlining. The people in this image are queueing on the Helicline which passes through the base of the landmark Trylon and leads into the Perisphere, containing Henry Dreyfuss’ City of Tomorrow and Raymond Loewy’s Transportation of Tomorrow exhibits. (John Van Noate collection)

Chemins de Fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée 4-4-0 no.C23, built by Ateliers de Paris in 1893. She carries extensive coupe-vent, or 'wind cutting' fairings. (Alon Siton collection)

Chemins de Fer de Paris à Lyon et à la Méditerranée 4-4-0 no.C23, built by Ateliers de Paris in 1893. She carries extensive coupe-vent, or 'wind cutting' fairings. (Alon Siton collection)

This is wind-cutter treatment, American style. Preserved McKeen petrol railcar no.22 is seen inside the Nevada Railroad Museum, Carson City. The first of these distinctive vehicles appeared in 1905. (Larry Meinstein)

This is wind-cutter treatment, American style. Preserved McKeen petrol railcar no.22 is seen inside the Nevada Railroad Museum, Carson City. The first of these distinctive vehicles appeared in 1905. (Larry Meinstein)

Der Fliegende Hamburger revolutionised rail travel in Germany from 1933, as it had to, to fend off growing competition from commercial aircraft and the new Autobahns. This example is preserved in the Deutsche Bahn Museum in Nuremberg. (Ian Black)

Der Fliegende Hamburger revolutionised rail travel in Germany from 1933, as it had to, to fend off growing competition from commercial aircraft and the new Autobahns. This example is preserved in the Deutsche Bahn Museum in Nuremberg. (Ian Black)

Epitomising the beauty, the glamour and the publicity value of streamlining, Gresley A4 no.4492 Dominion Of New Zealand, looks resplendent in her novel garter blue livery with stainless steel Gill Sans lettering. (Alon Siton collection)

Epitomising the beauty, the glamour and the publicity value of streamlining, Gresley A4 no.4492 Dominion Of New Zealand, looks resplendent in her novel garter blue livery with stainless steel Gill Sans lettering. (Alon Siton collection)

The Golden Age of Streamlining by Colin Alexander, is now available courtesy of Amberley Publishing: https://www.amberley-books.com/the-golden-age-of-streamlining.html